Middle High German

Template:Short description Template:Infobox language Middle High German (MHG; Template:Langx or Template:Lang; Template:Langx Template:IPA, shortened as Mhdt. or Mhd.) is the term for the form of High German spoken in the High Middle Ages. It is conventionally dated between 1050 and 1350, developing from Old High German (OHG) into Early New High German (ENHG). High German is defined as those varieties of German which were affected by the Second Sound Shift; the Middle Low German (MLG) and Middle Dutch languages spoken to the North and North West, which did not participate in this sound change, are not part of MHG.

While there is no standard MHG, the prestige of the Hohenstaufen court gave rise in the late 12th century to a supra-regional literary language (Template:Lang) based on Swabian, an Alemannic dialect. This historical interpretation is complicated by the tendency of modern editions of MHG texts to use normalised spellings based on this variety (usually called "Classical MHG"), which make the written language appear more consistent than it actually is in the manuscripts. Scholars are uncertain as to whether the literary language reflected a supra-regional spoken language of the courts.

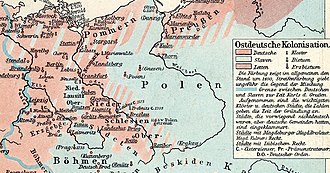

An important development in this period was the Template:Lang, the eastward expansion of German settlement beyond the Template:Lang line which marked the limit of Old High German. This process started in the 11th century, and all the East Central German dialects are a result of this expansion.

"Judeo-German", the precursor of the Yiddish language, is attested in the 12th–13th centuries, as a variety of Middle High German written in Hebrew characters.

Periodisation

Template:Legend Template:Legend Template:Legend Template:Legend Template:Legend

The Middle High German period is generally dated from 1050 to 1350.Template:SfnTemplate:SfnTemplate:SfnTemplate:Sfn An older view puts the boundary with (Early) New High German around 1500.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

There are several phonological criteria which separate MHG from the preceding Old High German period:Template:Sfn

- the weakening of unstressed vowels to Template:Angle bracket: OHG Template:Lang, MHG Template:Lang ("days")Template:Sfn

- the full development of umlaut and its use to mark a number of morphological categoriesTemplate:Sfn

- the devoicing of final stops: OHG Template:Lang > MHG Template:Lang ("day")Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Culturally, the two periods are distinguished by the transition from a predominantly clerical written culture, in which the dominant language was Latin, to one centred on the courts of the great nobles, with German gradually expanding its range of use.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn The rise of the Hohenstaufen dynasty in Swabia makes the South West the dominant region in both political and cultural terms.Template:Sfn

Demographically, the MHG period is characterised by a massive rise in population,Template:Sfn terminated by the demographic catastrophe of the Black Death (1348).Template:Sfn Along with the rise in population comes a territorial expansion eastwards (Template:Lang), which saw German-speaking settlers colonise land previously under Slavic control.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Linguistically, the transition to Early New High German is marked by four vowel changes which together produce the phonemic system of modern German, though not all dialects participated equally in these changes:Template:Sfn

- Diphthongisation of the long high vowels Template:IPA > Template:IPA: MHG Template:Lang > NHG Template:Lang ("skin")

- Monophthongisation of the high centering diphthongs Template:IPA > Template:IPA: MHG Template:Lang > NHG Template:Lang ("hat")

- lengthening of stressed short vowels in open syllables: MHG Template:Lang Template:IPA > NHG Template:Lang Template:IPA ("say")

- The loss of unstressed vowels in many circumstances: MHG Template:Lang > NHG Template:Lang ("lady")

The centres of culture in the ENHG period are no longer the courts but the towns.Template:Sfn

Dialects

The dialect map of Germany by the end of the Middle High German period was much the same as that at the start of the 20th century, though the boundary with Low German was further south than it now is:Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Central German (Mitteldeutsch)Template:Sfn

- West Central German (Westmitteldeutsch)

- Central Franconian (Mittelfränkisch)

- Ripuarian (Ripuarisch)

- Moselle Franconian (Moselfränkisch)

- Rhine Franconian (Rheinfränkisch)

- Hessian (Hessisch)

- Central Franconian (Mittelfränkisch)

- East Central German (Ostmitteldeutsch)

- Thuringian (Thüringisch)

- Upper Saxon (Obersächsisch)

- Silesian (Schlesisch)

- High Prussian (Hochpreußisch)

Upper German (Oberdeutsch)Template:Sfn

- East Franconian (Ostfränkisch)

- South Rhine Franconian (Süd(rhein)fränkisch)

- Alemannic (Alemannisch)

- North Alemannic (Nordalemannisch)

- Swabian (Schwäbisch)

- Low Alemannic (Niederalemannisch/Oberrheinisch)

- High Alemannic/South Alemannic (Hochalemannisch/Südalemannisch) )

- North Alemannic (Nordalemannisch)

- Bavarian (Bairisch)

- Northern Bavarian (Nordbairisch)

- Central Bavarian (Mittelbairisch)

- Southern Bavarian (Südbairisch)

With the exception of Thuringian, the East Central German dialects are new dialects resulting from the Template:Lang and arise towards the end of the period.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Writing system

Middle High German texts are written in the Latin alphabet. There was no standardised spelling, but modern editions generally standardise according to a set of conventions established by Karl Lachmann in the 19th century.Template:Sfn There are several important features in this standardised orthography which are not characteristics of the original manuscripts:

- the marking of vowel length is almost entirely absent from MHG manuscripts.Template:Sfn

- the marking of umlauted vowels is often absent or inconsistent in the manuscripts.Template:Sfn

- a curly-tailed z (Template:Angle bracket or Template:Angle bracket) is used in modern handbooks and grammars to indicate the Template:IPA or Template:IPA-like sound which arose from Germanic Template:IPA in the High German consonant shift. This character has no counterpart in the original manuscripts, which typically use Template:Angle bracket or Template:Angle bracket to indicate this sound.Template:Sfn

- the original texts often use Template:Angle bracket and Template:Angle bracket for the semi-vowels Template:IPA and Template:IPA.Template:Sfn

A particular problem is that many manuscripts are of much later date than the works they contain; as a result, they bear the signs of later scribes having modified the spellings, with greater or lesser consistency, in accord with conventions of their time.Template:Sfn In addition, there is considerable regional variation in the spellings that appear in the original texts, which modern editions largely conceal.Template:Sfn

Vowels

The standardised orthography of MHG editions uses the following vowel spellings:Template:Sfn

- Short vowels: Template:Angle bracket and the umlauted vowels Template:Angle bracket

- Long vowels: Template:Angle bracket and the umlauted vowels Template:Angle bracket

- Diphthongs: Template:Angle bracket; and the umlauted diphthongs Template:Angle bracket

Grammars (as opposed to textual editions) often distinguish between Template:Angle bracket and Template:Angle bracket, the former indicating the mid-open Template:IPA which derived from Germanic Template:IPA, the latter (often with a dot beneath it) indicating the mid-close Template:IPA which results from primary umlaut of short Template:IPA. No such orthographic distinction is made in MHG manuscripts.Template:Sfn

Consonants

The standardised orthography of MHG editions uses the following consonant spellings:Template:Sfn

- Stops: Template:Angle bracket

- Affricates: Template:Angle bracket

- Fricatives: Template:Angle bracket

- Nasals: Template:Angle bracket

- Liquids: Template:Angle bracket

- Semivowels: Template:Angle bracket

Phonology

The charts show the vowel and consonant systems of classical MHG. The spellings indicated are the standard spellings used in modern editions; there is much more variation in the manuscripts.

Vowels

Short and long Vowels

Notes:

- Not all dialects distinguish the three unrounded mid front vowels.

- It is probable that the short high and mid vowels are lower than their long equivalents, as in Modern German, but that is impossible to establish from the written sources.

- The Template:Angle bracket found in unstressed syllables may indicate Template:IPA or schwa Template:IPA.

Diphthongs

MHG diphthongs are indicated by the spellings Template:Angle bracket, Template:Angle bracket, Template:Angle bracket, Template:Angle bracket and Template:Angle bracket, Template:Angle bracket, Template:Angle bracket, and they have the approximate values of Template:IPA, Template:IPA, Template:IPA, Template:IPA, Template:IPA, Template:IPA, Template:IPA, respectively.

Consonants

- Precise information about the articulation of consonants is impossible to establish and must have varied between dialects.

- In the plosive and fricative series, if there are two consonants in a cell, the first is fortis and the second lenis. The voicing of lenis consonants varied between dialects.

- There are long consonants, and the following double consonant spellings indicate not vowel length, as they do in Modern German orthography, but rather genuine double consonants: pp, bb, tt, dd, ck (for Template:IPA), gg, ff, ss, zz, mm, nn, ll, rr.

- It is reasonable to assume that Template:IPA has an allophone Template:IPA after back vowels, as in Modern German.

- The original Germanic fricative s was in writing usually clearly distinguished from the younger fricative z that evolved from the High German consonant shift. The sounds of both letters seem not to have merged before the 13th century. Since s later came to be pronounced Template:IPA before other consonants (as in Stein Template:IPA, Speer Template:IPA, Schmerz Template:IPA (original smerz) or the southwestern pronunciation of words like Ast Template:IPA), it seems safe to assume that the actual pronunciation of Germanic s was somewhere between Template:IPA and Template:IPA, most likely about Template:IPAblink, in all Old High German until late Middle High German. A word like swaz, "whatever", would thus never have been Template:IPA but rather Template:IPA, later (13th century) Template:IPA, Template:IPA.

Grammar

Pronouns

Middle High German pronouns of the first person refer to the speaker; those of the second person refer to an addressed person; and those of the third person refer to a person or thing of which one speaks. The pronouns of the third person may be used to replace nominal phrases. These have the same genders, numbers and cases as the original nominal phrase.

Personal pronouns

| 1st sg | 2nd sg | 3rd sg | 1st pl | 2nd pl | 3rd pl | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang / Template:Lang |

| Accusative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang(ich) | Template:Lang | ||

| Dative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| Genitive | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | |

Possessive pronouns

The possessive pronouns Template:Lang are used like adjectives and hence take on adjective endings following the normal rules.

Articles

The inflected forms of the article depend on the number, the case and the gender of the corresponding noun. The definite article has the same plural forms for all three genders.

Definite article (strong)

| Case | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang / Template:Lang |

| Accusative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | ||

| Dative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | |

| Genitive | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | ||

| Instrumental | Template:Lang | |||

The instrumental case, only existing in the neuter singular, is used only with prepositions: Template:Lang, Template:Lang, etc. In all the other genders and in the plural it is substituted with the dative: Template:Lang, Template:Lang, Template:Lang.

Nouns

Middle High German nouns were declined according to four cases (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative), two numbers (singular and plural) and three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter), much like Modern High German, though there are several important differences.

Strong nouns

| Template:Lang day m. |

Template:Lang gift f. |

Template:Lang word n. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| Accusative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | |||

| Genitive | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| Dative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | |

| Template:Lang guest m. |

Template:Lang strength f. |

Template:Lang lamb n. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| Accusative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | |||

| Genitive | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| Dative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

Weak nouns

| Template:Lang (male) cousin m. |

Template:Lang tongue f. |

Template:Lang heart n. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| Accusative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | ||||

| Genitive | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| Dative | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

Verbs

Template:Main Verbs were conjugated according to three moods (indicative, subjunctive (conjunctive) and imperative), three persons, two numbers (singular and plural) and two tenses (present tense and preterite) There was a present participle, a past participle and a verbal noun that somewhat resembles the Latin gerund, but that only existed in the genitive and dative cases.

An important distinction is made between strong verbs (that exhibited ablaut) and weak verbs (that didn't).

Furthermore, there were also some irregular verbs.

Strong verbs

The present tense conjugation went as follows:

| Template:Lang to take | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicative | Subjunctive | |

| 1. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 2. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 3. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 1. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 2. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 3. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

- Imperative: 2.sg.: Template:Lang, 2.pl.: Template:Lang

- Present participle: Template:Lang

- Infinitive: Template:Lang

- Verbal noun: genitive: Template:Lang, dative: Template:Lang

The bold vowels demonstrate umlaut; the vowels in brackets were dropped in rapid speech.

The preterite conjugation went as follows:

| Template:Lang to have taken | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicative | Subjunctive | |

| 1. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 2. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 3. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 1. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 2. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 3. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

- Past participle: Template:Lang

Weak verbs

The present tense conjugation went as follows:

| Template:Lang to seek | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicative | Subjunctive | |

| 1. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 2. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 3. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 1. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 2. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 3. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

- Imperative: 2.sg: Template:Lang, 2.pl: Template:Lang

- Present participle: Template:Lang

- Infinitive: Template:Lang

- Verbal noun: genitive: Template:Lang, dative: Template:Lang

The vowels in brackets were dropped in rapid speech.

The preterite conjugation went as follows:

| Template:Lang to have sought | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicative | Subjunctive | |

| 1. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 2. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 3. sg. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 1. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 2. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

| 3. pl. | Template:Lang | Template:Lang |

- Past participle: Template:Lang

Vocabulary

In the Middle High German period, the rise of a courtly culture and the changing nature of knighthood was reflected in changes to the vocabulary.Template:Sfn Since the impetus for this set of social changes came largely from France, many of the new words were either loans from French or influenced by French terms.

The French loans mainly cover the areas of chivalry, warfare and equipment, entertainment, and luxury goods:Template:Sfn

- MHG Template:Lang < OF Template:Lang (NHG Template:Lang, "adventure")

- MHG Template:Lang < OF Template:Lang (NHG Template:Lang, "prize, reward")

- MHG Template:Lang < OF Template:Lang (NHG Template:Lang, "lance")

- MHG Template:Lang < OF Template:Lang (NHG Template:Lang, "palace")

- MHG Template:Lang < OF Template:Lang (NHG Template:Lang, "festival, feast")

- MHG Template:Lang < OF Template:Lang (NHG Template:Lang, "paint brush")

- MHG Template:Lang < OF Template:Lang (NHG Template:Lang, "velvet")

- MHG Template:Lang < OF Template:Lang (NHG Template:Lang, "raisin")

Two highly productive suffixes were borrowed from French in this period:

- The noun suffix -Template:Lang is seen initially in borrowings from French such as Template:Lang ("retinue, household") and then starts to be combined with German nouns to produce, for example, Template:Lang ("hunting") from Template:Lang ("huntsman"), or Template:Lang ("medicine ") from Template:Lang ("doctor"). With the Early New High German diphthongization the suffix became /ai/ (spelling <ei>) giving NHG Template:Lang, Template:Lang.Template:Sfn

- The verb suffix -Template:Lang resulted from adding the German infinitive suffix -en to the Old French infinitive endings -er/ir/ier. Initially, this was just a way of integrating French verbs into German syntax, but the suffix became productive in its own right and was added to non-French roots: MHG Template:Lang is based on OF Template:Lang ("to ride a horse"), but Template:Lang ("to cut in half") has no French source.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Sample texts

Iwein

The text is the opening of Hartmann von Aue's Iwein (Template:Circa)

| Middle High GermanTemplate:Sfn | English translation | |

|---|---|---|

Swer an rehte güete |

[1] |

Whoever to true goodness |

Commentary: This text shows many typical features of Middle High German poetic language. Most Middle High German words survive into modern German in some form or other: this passage contains only one word (Template:Lang 'say' 14) which has since disappeared from the language. But many words have changed their meaning substantially. Template:Lang (6) means 'state of mind' (cognates with mood), where modern German Template:Lang means courage. Template:Lang (3) can be translated with 'honour', but is quite a different concept of honour from modern German Template:Lang; the medieval term focuses on reputation and the respect accorded to status in society.Template:Sfn

Nibelungenlied

The text is the opening strophe of the Template:Lang (Template:Circa).

Middle High GermanTemplate:Sfn

Uns ist in alten mæren wunders vil geseit

von helden lobebæren, von grôzer arebeit,

von freuden, hôchgezîten, von weinen und von klagen,

von küener recken strîten muget ir nu wunder hœren sagen.Modern German translationTemplate:Sfn

In alten Erzählungen wird uns viel Wunderbares berichtet

von ruhmreichen Helden, von hartem Streit,

von glücklichen Tagen und Festen, von Schmerz und Klage:

vom Kampf tapferer Recken: Davon könnt auch Ihr nun Wunderbares berichten hören.English translationTemplate:Sfn

In ancient tales many marvels are told us

of renowned heroes, of great hardship

of joys, festivities, of weeping and lamenting

of bold warriors' battles — now you may hear such marvels told!

Commentary: All the MHG words are recognizable from Modern German, though Template:Lang ("tale") and Template:Lang ("warrior") are archaic and Template:Lang ("praiseworthy") has given way to Template:Lang. Words which have changed in meaning include Template:Lang, which means "strife" or "hardship" in MHG, but now means "work", and Template:Lang ("festivity") which now, as Template:Lang, has the narrower meaning of "wedding".Template:Sfn

Erec

The text is from the opening of Hartmann von Aue's Erec (Template:Circa). The manuscript (the Ambraser Heldenbuch) dates from 1516, over three centuries after the composition of the poem.

| Original manuscriptTemplate:Sfn | Edited textTemplate:Sfn | English translationTemplate:Sfn | |

|---|---|---|---|

5 |

nu riten ſÿ vnlange friſt |

nû riten si unlange vrist |

Now they had not been riding together |

Literature

Template:Main The following are some of the main authors and works of MHG literature: Template:Div col

See also

References

Bibliography

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite web

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite encyclopedia

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite encyclopedia

- Template:Cite encyclopedia

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

Further reading

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Jones, Howard; Jones, Martin H. (2019). The Oxford Guide to Middle High German, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. {{#invoke:CS1 identifiers|main|_template=isbn}}.

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Walshe, M.O'C. (1974). A Middle High German Reader: With Grammar, Notes and Glossary, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. {{#invoke:CS1 identifiers|main|_template=isbn}}.

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Wright, Joseph & Walshe, M.O'C. (1955). Middle High German Primer, 5th edn., Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. The foregoing link is to a TIFF and PNG format. See also the Germanic Lexicon Project's edition, which is in HTML as well as the preceding formats.