Raynald of Châtillon

Template:Short description Template:Featured article

Template:Use dmy dates Template:Infobox royalty

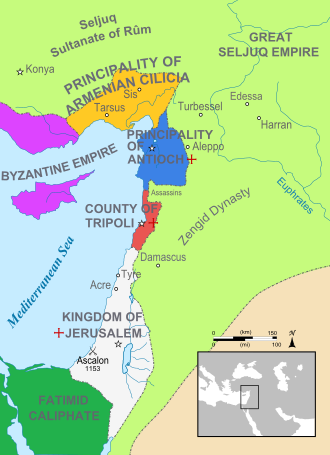

Raynald of Châtillon (Template:Circa 1124Template:Spnd4 July 1187), also known as Reynald, Reginald, or Renaud, was Prince of Antioch—a crusader state in the Middle East—from 1153 to 1160 or 1161, and Lord of Oultrejordain—a large fiefdom in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem—from 1175 until his death, ruling both territories Template:Lang ('by right of wife'). The second son of a French noble family, he joined the Second Crusade in 1147, and settled in Jerusalem as a mercenary. Six years later, he married Constance, Princess of Antioch, although her subjects regarded the marriage as a mesalliance.

Always in need of funds, Raynald tortured Aimery of Limoges, Latin Patriarch of Antioch, who had refused to pay a subsidy to him. He launched a plundering raid in Cyprus in 1156, causing great destruction in Byzantine territory. Four years later, Manuel I Komnenos, the Byzantine Emperor, led an army towards Antioch, forcing Raynald to accept Byzantine suzerainty. Raynald was raiding the valley of the river Euphrates in 1160 or 1161 when the governor of Aleppo captured him at Marash. He was released for a large ransom in 1176 but did not return to Antioch, because his wife had died in the interim. He married Stephanie of Milly, the wealthy heiress of Oultrejordain. Since King Baldwin IV of Jerusalem had also granted Hebron to him, Raynald became one of the wealthiest barons in the kingdom. After Baldwin, who suffered from leprosy, made him regent in 1177, Raynald led the crusader army that defeated Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria, at the Battle of Montgisard. In control of the caravan routes between Egypt and Syria, he was the only Christian leader to pursue an offensive policy against Saladin, by making plundering raids against the caravans travelling near his domains. After Raynald's newly constructed fleet plundered the coast of the Red Sea in early 1183, threatening the route of Muslim pilgrims to Mecca, Saladin pledged that he would never forgive him.

Raynald was a firm supporter of Baldwin IV's sister, Sybilla, and her husband, Guy of Lusignan, during conflicts regarding Baldwin IV's succession. Sibylla and Guy were able to seize the throne in 1186 due to Raynald's co-operation with her uncle, Joscelin III of Courtenay. In spite of a truce between Saladin and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Raynald attacked a caravan travelling from Egypt to Syria in late 1186 or early 1187, claiming that the truce was not binding upon him. After Raynald refused to pay compensation, Saladin invaded the kingdom and annihilated the crusader army in the Battle of Hattin. Raynald was captured on the battlefield. Saladin personally beheaded him after he refused to convert to Islam. Many historians have regarded Raynald as an irresponsible adventurer whose lust for booty caused the fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. On the other hand, the historian Bernard Hamilton says that he was the only crusader leader who tried to prevent Saladin from unifying the nearby Muslim states.

Early years

Raynald was the younger son of Hervé II, Lord of Donzy in France.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn In older historiography, Raynald was thought to have been the son of Geoffrey, Count of Gien,Template:Sfn but the historian Jean Richard demonstrated Raynald's kinship with the lords of Donzy.Template:Refn They were influential noblemen in the Duchy of Burgundy (in present-day eastern France), who claimed descent from the Palladii, a prominent Gallo-Roman aristocratic family during the Later Roman period.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Raynald's mother, whose name is not known, was a daughter of Hugh the White, Lord of La Ferté-Milon.Template:Sfn

Born around 1124, Raynald inherited the lordship of Châtillon-sur-Loire.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Years later, he would complain in a letter to Louis VII of France that a part of his patrimony was "violently and unjustly confiscated". The historian Malcolm Barber says that probably this event prompted Raynald to leave his homeland for the crusader states.Template:RefnTemplate:Sfn According to modern historians, Raynald came to the Kingdom of Jerusalem in LouisTemplate:NbspVII's army during the Second Crusade in 1147,Template:Refn and stayed behind when the French abandoned the military campaign two years later.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Early in 1153, he is known to have fought in the army of Baldwin III of Jerusalem during the siege of Ascalon.Template:Sfn

The 12th-century historian William of Tyre, who was Raynald's political opponent, describes him as "a kind of mercenary knight", emphasising the distance between Raynald and Princess Constance of Antioch, whom Raynald unexpectedly engaged to marry before the end of the siege.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Constance, the only daughter and successor of Bohemond II of Antioch, had been widowed when her husband, Raymond of Poitiers, fell in the Battle of Inab on 28Template:NbspJune 1148.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn To secure the defence of Antioch, BaldwinTemplate:NbspIII (who was Constance's cousin) led his army to Antioch at least three times during the following years. He tried to persuade Constance to remarry, but she did not accept his candidates. She also refused John Roger, whom the Byzantine emperor, Manuel I Komnenos, had proposed to be her husband.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Raynald and Constance kept their betrothal a secret until Baldwin gave his permission for their marriage.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn According to the historian Andrew D. Buck, they needed a royal permission because Raynald was in Baldwin's service.Template:Sfn The early-13th-century chronicle known as the Template:Lang states that Baldwin happily consented to the marriage because it freed him from his obligation to "defend a land" (namely Antioch) "which was so far away" from his kingdom.Template:Sfn

Prince of Antioch

After Baldwin granted his consent, Constance married Raynald.Template:SfnTemplate:SfnTemplate:Sfn He was installed as prince in or shortly before May 1153.Template:Sfn In that month, he confirmed the privileges of the Venetian merchants.Template:Sfn William of Tyre records that his subjects were astonished that their "famous, powerful and well-born" princess married a man of low status.Template:Sfn No coins struck for Raynald have survived. According to Buck, this indicates that Raynald's position was relatively weak. Whereas Raymond of Poitiers had issued around half of his charters without a reference to Constance, Raynald always mentioned that he made the decision with his wife's consent.Template:Sfn Raynald did control appointments to the highest offices: he made Geoffrey Jordanis the constable and Geoffrey Falsard the duke of Antioch.Template:RefnTemplate:Sfn

The Norman chronicler Robert of Torigni writes that Raynald seized three fortresses from the Aleppans soon after his accession, but does not name them.Template:Sfn Aimery of Limoges, the wealthy Latin patriarch of Antioch, did not hide his dismay at Constance's second marriage. He even refused to pay a subsidy to Raynald, although Raynald, as Barber underlines, "was in dire need of money". In retaliation for Aimery's refusal, Raynald arrested and tortured him in the summer of 1154, forcing him to sit naked and covered with honey in the sun, before imprisoning him. Aimery was only released on BaldwinTemplate:NbspIII's demand, but he soon left Antioch for Jerusalem.Template:SfnTemplate:SfnTemplate:Sfn Surprisingly, Raynald was not excommunicated for his abuse of a high-ranking cleric. Buck argues that Raynald could avoid the punishment because of Aimery's previous disputes with the papacy over the Archbishopric of Tyre. Instead, Aimery excommunicated Raynald on the demand of the papacy in 1154 as a consequence of a conflict between Antioch and Genoa.Template:Sfn

Emperor Manuel, who claimed suzerainty over Antioch, sent his envoys to Raynald,Template:Refn proposing to recognize him as the new prince if he launched a campaign against the Armenians of Cilicia, who had risen up against Byzantine rule.Template:Refn He also promised that he would compensate Raynald for the expenses of the campaign.Template:Sfn After Raynald defeated the Armenians at Alexandretta in 1155, the Knights Templar took control of the region of the Syrian Gates that the Armenians had recently invaded.Template:Sfn Although the sources are unclear, Runciman and Barber agree that it was Raynald who granted the territory to them.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Always in need of funds, Raynald urged Manuel to send the promised subsidy to him, but Manuel failed to pay the money.Template:Sfn Raynald made an alliance with the Armenian lord Thoros II of Cilicia. They attacked Cyprus, plundering the prosperous Byzantine island for three weeks in early 1156.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Hearing rumours of an imperial fleet approaching the island, they left Cyprus, but only after they had forced all Cypriots to ransom themselves, with the exception of the wealthiest individuals (including Manuel's nephew, John Doukas Komnenos), whom they carried off to Antioch as hostages.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Taking advantage of the presence of Count Thierry of Flanders and his army in the Holy Land and an earthquake that had destroyed most towns in Northern Syria, BaldwinTemplate:NbspIII of Jerusalem invaded the Muslim territories in the valley of the Orontes River in the autumn of 1157.Template:Sfn Raynald joined the royal army, and they laid siege to Shaizar.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn At this point, Shaizar was held by the Shi'ite Assassins, but before the earthquake it had been the seat of the Sunnite Munqidhites who paid an annual tribute to Raynald.Template:Sfn Baldwin was planning to grant the fortress to Thierry of Flanders, but Raynald demanded that the count should pay homage to him for the town. After Thierry sharply refused to swear fealty to an upstart, the crusaders abandoned the siege.Template:Sfn They marched on Harenc (present-day Harem, Syria), which had been an Antiochene fortress before Nur ad-Din captured it in 1150.Template:Sfn After the crusaders captured Harenc in February 1158, Raynald granted it to Raynald of Saint-Valery from Flanders.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Emperor Manuel unexpectedly invaded Cilicia, forcing ThorosTemplate:NbspII to seek refuge in the mountains in December 1158.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Unable to resist a full-scale Byzantine invasion, Raynald hurried to Mamistra to voluntarily make his submission to the emperor.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn On Manuel's demand, Raynald and his retainers walked barefoot and bareheaded through the streets of the town to the imperial tent where he prostrated himself, begging for mercy.Template:Sfn William of Tyre stated that "the glory of the Latin world was put to shame" on this occasion, because envoys from the nearby Muslim and Christian rulers were also present at Raynald's humiliation.Template:Sfn Manuel demanded that a Greek patriarch be installed at Antioch. Although his demand was not accepted, documentary evidence indicates that Gerard, the Catholic bishop of Latakia, was forced to move to Jerusalem.Template:Sfn Raynald had to promise that he would allow a Byzantine garrison to stay in the citadel whenever it was required and would send a troop to fight in the Byzantine army.Template:Sfn Before long, BaldwinTemplate:NbspIII of Jerusalem persuaded Manuel to consent to the return of the Latin patriarch, Aimery, to Antioch, instead of installing a Greek patriarch. When the emperor entered Antioch with much pomp and ceremony on 12Template:NbspApril 1159, Raynald held the bridle of Manuel's horse.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Manuel left the town eight days later.Template:Sfn

Raynald made a plundering raid in the valley of the river Euphrates at Marash to seize cattle, horses and camels from the local peasants in November 1160 or 1161.Template:SfnTemplate:SfnTemplate:Sfn Majd ad-Din, Nur ad-Din's commander of Aleppo, gathered his troops (10,000 people, according to the contemporary historian Matthew of Edessa), and attacked Raynald and his retinue on the way back to Antioch.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Raynald tried to fight, but he was unhorsed and captured. He was sent to Aleppo where he was put in jail.Template:Sfn

Captivity and release

Almost nothing is known about Raynald's life while he was imprisoned for fifteen years.Template:Sfn He shared his prison with Joscelin III of Courtenay, the titular count of Edessa, who had been captured a couple of months before him.Template:Sfn In Raynald's absence, Constance wanted to rule alone, but BaldwinTemplate:NbspIII of Jerusalem made Patriarch Aimery regent for her fifteen-year-old son (Raynald's stepson), Bohemond III of Antioch.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Constance died around 1163, shortly after her son reached the age of majority.Template:Sfn Her death deprived Raynald of his claim to Antioch.Template:Sfn However, he had become an important personality, with prominent family connections, as his stepdaughter, Maria of Antioch, married Emperor Manuel in 1161, and his own daughter, Agnes, became the wife of Béla III of Hungary.Template:Sfn

Nur ad-Din died unexpectedly in 1174. His underage son as-Salih Ismail al-Malik succeeded him, and Nur ad-Din's Template:Lang ('slave-soldier') Gümüshtekin assumed the regency for him in Aleppo. Being unable to resist attacks by Saladin, Gümüshtekin sought the support of Raynald's stepson Bohemond III of Antioch, and on his request released Raynald along with Joscelin of Courtenay and all other Christian prisoners in 1176.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Raynald's ransom, fixed at 120,000 gold dinars, reflected his prestige.Template:Sfn It was most probably paid by Emperor Manuel, according to Barber and Hamilton.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Raynald came to Jerusalem with Joscelin before 1Template:NbspSeptember 1176,Template:Sfn where he became a close ally of Joscelin's sister, Agnes of Courtenay.Template:Sfn She was the mother of the young Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, who suffered from leprosy.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Hugo Etherianis, who lived in Constantinople after about 1165, mentioned in the preface of his work About the Procession of the Holy Spirit, that he had asked "Prince Raynald" to deliver a copy of the work to Aimery of Limoges.Template:Sfn Hamilton writes that these words suggest that Raynald led the embassy that BaldwinTemplate:NbspIV sent to Constantinople to confirm an alliance between Jerusalem and the Byzantine Empire against Egypt towards the end of 1176.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Lord of Oultrejordain

First years

After his return from Constantinople early in 1177, Raynald married Stephanie of Milly, the lady of Oultrejordain, and BaldwinTemplate:NbspIV also granted him Hebron.Template:Sfn The first extant charter styling Raynald as "Lord of Hebron and Montréal" was issued in November 1177.Template:Sfn He owed service of 60 knights to the Crown, showing that he had become one of the wealthiest barons of the realm.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn From his castles at Kerak and Montréal, he controlled the routes between the two main parts of Saladin's empire, Syria and Egypt.Template:Sfn Raynald and BaldwinTemplate:NbspIV's brother-in-law, William of Montferrat, jointly granted large estates to Rodrigo Álvarez, the founder of the Order of Mountjoy, to strengthen the defence of the southern and eastern frontier of the kingdom.Template:Sfn After William of Montferrat died in June 1177, the king made Raynald regent of the kingdom.Template:Sfn

Baldwin IV's cousin Count Philip I of Flanders came to the Holy Land at the head of a crusader army in early August 1177.Template:Sfn The king offered him the regency, but Philip refused the offer, saying that he did not want to stay in the kingdom.Template:Sfn Philip declared that he was "willing to take orders" from anybody, but he protested when Baldwin confirmed Raynald's position as "regent of the kingdom and of the armies" as he thought that a military commander without special powers should lead the army.Template:Sfn Philip left the kingdom a month after his arrival.Template:Sfn

Saladin invaded the region of Ascalon, but the royal army launched an attack on him in the Battle of Montgisard on 25Template:NbspNovember, leading to his defeat.Template:Sfn William of Tyre and Ernoul attributed the victory to the king, but Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad and other Muslim authors recorded that Raynald was the supreme commander.Template:Sfn Saladin himself referred to the battle as a "major defeat which God mended with the famous battle of Hattin",[1] according to Baha ad-Din.Template:Sfn

Raynald signed a majority of royal charters between 1177 and 1180, with his name always first among signatories, showing that he was the king's most influential official during this period.Template:Sfn Raynald became one of the principal supporters of Guy of Lusignan, who married the king's elder sister, Sybilla, in early 1180, although many barons of the realm had opposed the marriage.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn The king's half sister, Isabella (whose stepfather, Balian of Ibelin, was Guy of Lusignan's opponent), was engaged to Raynald's stepson, Humphrey IV of Toron, in autumn 1180.Template:Sfn

BaldwinTemplate:NbspIV dispatched Raynald, along with Heraclius, the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, to mediate a reconciliation between Bohemond III of Antioch and Patriarch Aimery in early 1181.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn The same year, Roupen III, Lord of Cilician Armenia, married Raynald's stepdaughter, Isabella of Toron.Template:Sfn

Fights against Saladin

Raynald was the only Christian leader who fought against Saladin in the 1180s.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn The contemporary chronicler Ernoul mentions two raids that Raynald made against caravans travelling between Egypt and Syria, breaking the truce.Template:Sfn Modern historians debate whether Raynald's military actions sprang from a desire for booty,Template:Sfn or were deliberate maneuvers to prevent Saladin from annexing new territories.Template:Sfn After as-Salih died on 18Template:NbspNovember 1181, Saladin tried to seize Aleppo, but Raynald stormed into Saladin's territory, reaching as far as Tabuk on the route between Damascus and Mecca.Template:Sfn Saladin's nephew, Farrukh Shah, invaded Oultrejordain instead of attacking Aleppo to compel Raynald to return from the Arabian Desert.Template:Sfn Before long, Raynald seized a caravan and imprisoned its members.Template:Sfn On Saladin's protest, BaldwinTemplate:NbspIV ordered Raynald to free them, but Raynald refused.Template:Sfn His defiance annoyed the king, enabling Raymond III of Tripoli's partisans to reconcile him with the monarch.Template:Sfn A close relative of Baldwin, Raymond had assumed the regency in 1174 but was banned from the kingdom for allegedly plotting against the ailing king.Template:Sfn Raymond's return to the royal court put an end to Raynald's paramount position. After accepting the new situation, Raynald cooperated with the king and Raymond during the fights against Saladin in the summer of 1182.Template:Sfn

Saladin revived the Egyptian naval force and tried to capture Beirut, but his ships were forced to retreat.Template:Sfn Raynald ordered the building of at least five ships in Oultrejordain. They were carried across the Negev desert to the Gulf of Aqaba at the northern end of the Red Sea in January or February 1183.Template:SfnTemplate:SfnTemplate:Sfn He captured the fort of Ayla (present-day Eilat in Israel), and attacked the Egyptian fortress on Pharaoh's Island. Part of his fleet made a plundering raid along the coasts against ships delivering Muslim pilgrims and goods, threatening the security of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Raynald left the island, but his fleet continued the siege.Template:Sfn Saladin's brother, al-Adil, the governor of Egypt, dispatched a fleet to the Red Sea. The Egyptians relieved Pharaoh's Island and destroyed the Christian fleet. Some of the soldiers were captured near Medina because they landed either to escape or to attack the city. Raynald's men were executed, and Saladin took an oath that he would never forgive him.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Though Raynald's naval expedition "showed a remarkable degree of initiative" according to Hamilton, most modern historians agree that it contributed to the unification of Syria and Egypt under Saladin's rule.Template:Sfn Saladin captured Aleppo in June 1183, completing the encirclement of the crusader states.Template:Sfn

Baldwin IV, who had become seriously ill, made Guy of Lusignan regent in October 1183.Template:Sfn Within a month, Baldwin had dismissed Guy, and had Guy's five-year-old stepson, Baldwin V, crowned king in association with himself.Template:Sfn Raynald was not present at the child's coronation, because he was at the wedding of his stepson, Humphrey, and BaldwinTemplate:NbspIV's sister, Isabella, in Kerak.Template:Sfn Saladin unexpectedly invaded Oultrejordain, forcing the local inhabitants to seek refuge in Kerak.Template:Sfn After Saladin broke into the town, Raynald only managed to escape to the fortress because one of his retainers had hindered the attackers from seizing the bridge between the town and the castle.Template:Sfn Saladin laid siege to Kerak.Template:Sfn According to Ernoul, Raynald's wife sent dishes from the wedding to Saladin, persuading him to stop bombarding the tower where her son and his wife stayed.Template:Sfn After envoys from Kerak informed BaldwinTemplate:NbspIV of the siege, the royal army left Jerusalem for Kerak under the command of the king and RaymondTemplate:NbspIII of Tripoli.Template:Sfn Saladin abandoned the siege before their arrival on 4Template:NbspDecember.Template:Sfn On Saladin's order, Izz ad-Din Usama had a fortress built at Ajloun, near the northern border of Raynald's domains.Template:Sfn

Kingmaker

Baldwin IV died in early 1185.Template:Sfn His successor, the child BaldwinTemplate:NbspV, died in late summer 1186.Template:Sfn The High Court of Jerusalem had ruled that neither BaldwinTemplate:NbspV's mother, Sybilla (who was Guy of Lusignan's wife), nor her sister, Isabella (who was the wife of Raynald's stepson), could be crowned without the decision of the pope, the Holy Roman Emperor, and the kings of France and England on BaldwinTemplate:NbspV's lawful successor.Template:Sfn However, Sybilla's uncle, JoscelinTemplate:NbspIII of Courtenay, took control of Jerusalem with the support of Raynald and other influential prelates and royal officials.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Raynald urged the townspeople to accept Sybilla as the lawful monarch, according to the Template:Lang.Template:Sfn RaymondTemplate:NbspIII of Tripoli, and his supporters tried to prevent her coronation and reminded her partisans of the decision of the High Court.Template:Sfn Ignoring their protest, Raynald and Gerard of Ridefort, Grand Master of the Knights Templar, accompanied Sybilla to the Holy Sepulchre, where she was crowned.Template:Sfn She also arranged the coronation of her husband, although he was unpopular even among her supporters.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Her opponents tried to persuade Raynald's stepson, Humphrey, to claim the crown on his wife's behalf, but Humphrey deserted them and swore fealty to Sybilla and Guy.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Raynald headed the list of secular witnesses in four royal charters issued between 21Template:NbspOctober 1186 and 7Template:NbspMarch 1187, showing that he had become a principal figure in the new king's court.Template:Sfn

Ali ibn al-Athir and other Muslim historians stated that Raynald made a separate truce with Saladin in 1186.Template:Sfn This "seems unlikely to be true", according to Hamilton, because the truce between the Kingdom of Jerusalem and Saladin legally covered Raynald's domains as they formed a large fiefdom in the kingdom.Template:Sfn In late 1186 or early 1187, a rich caravan travelled through Oultrejordain from Egypt to Syria.Template:Sfn Ali ibn al-Athir mentioned that a group of armed men accompanied the caravan.Template:Sfn Raynald seized the caravan, possibly because he regarded the presence of soldiers as a breach of the truce, according to Hamilton.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn He took all the merchants and their families prisoner, seized a large amount of booty, and refused to receive envoys from Saladin demanding compensation.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Saladin sent his envoys to Guy of Lusignan, who accepted his demands.Template:Sfn However, Raynald refused to obey the king, stating in the words of the Template:Lang that "he was lord of his land, just as Guy was lord of his, and he had no truces with the Saracens". For Barber, Raynald's disobedience indicates that the kingdom was "on the brink of breaking up into a collection of semi-autonomous fiefdoms" under Guy's rule.Template:Sfn Saladin proclaimed a Template:Lang (or holy war) against the kingdom, taking an oath that he would personally kill Raynald for breaking the truce.Template:Sfn The historian Paul M. Cobb remarks that Saladin "badly needed a victory against the Franks to silence those who criticized him for spending so much time at war with his fellow Muslims".Template:Sfn

Capture and execution

The Template:Lang incorrectly claims that Saladin's sister was also among the prisoners taken by Raynald when he seized the caravan.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn She returned from Mecca to Damascus in a separate pilgrim caravan in March 1187.Template:Sfn To protect her against an attack by Raynald, Saladin escorted the pilgrims while they were travelling near Oultrejordain.Template:Sfn Saladin stormed into Oultrejordain on 26Template:NbspApril and pillaged Raynald's domains for a month.Template:Sfn Thereafter, Saladin marched to Ashtara on the road between Damascus and Tiberias, where the troops coming from all parts of his realm assembled.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

The Christian forces assembled at Sepphoris.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Raynald and Gerard of Ridefort persuaded Guy of Lusignan to take the initiative and attack Saladin's army, although RaymondTemplate:NbspIII of Tripoli had tried to persuade the king to avoid a direct fight with it.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn During the debate, Raynald accused Raymond of Tripoli of co-operating with the enemy.Template:Sfn Raynald and Rideford had fatally misjudged the situation.Template:Sfn Saladin inflicted a crushing defeat on the crusaders in the Battle of Hattin on 4Template:NbspJuly, and most commanders of the Christian army were captured on the battlefield.Template:Sfn

Guy of Lusignan and Raynald were among the prisoners who were brought before Saladin.Template:Sfn Saladin handed a cup of iced rose water to Guy.Template:Sfn After drinking from the cup, the king handed it to Raynald.Template:Sfn Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani (who was present) recorded that Raynald drank from the cup.Template:Sfn Since customary law prescribed that a man who gave food or drink to a prisoner could not kill him, Saladin pointed out that it was Guy who had given the cup to Raynald.Template:Sfn After calling Raynald to his tent,Template:Sfn Saladin accused him of many crimes (including brigandage and blasphemy), offering him to choose between conversion to Islam or death, according to Imad ad-Din and Ibn al-Athir.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn After Raynald flatly refused to convert, Saladin took a sword and struck Raynald with it.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn As Raynald fell to the ground, Saladin beheaded him.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn The reliability of the reports of Saladin's offer to Raynald is subject to scholarly debate, because the Muslim authors who recorded them may have only wanted to improve Saladin's image.Template:Sfn Ernoul's chronicle and the Template:Lang recount the events ending with Raynald's execution in almost the same language as the Muslim authors.Template:Sfn However, according to Ernoul's chronicle, Raynald refused to drink from the cup that Guy of Lusignan handed to him.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn According to Ernoul, Raynald's head was struck off by Saladin's soldiers and it was brought to Damascus to be "dragged along the ground to show the Saracens, whom the prince had wronged, that vengeance had been exacted".Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn Baha ad-Din also wrote that Raynald's fate shocked Guy of Lusignan, but Saladin soon comforted him, stating that "A king does not kill a king, but that man's perfidy and insolence went too far".Template:Sfn

Family

Raynald's first wife, Constance of Antioch (born in 1128), was the only daughter of Bohemond II of Antioch and Alice of Jerusalem.Template:Sfn Constance succeeded her father in Antioch in 1130.Template:Sfn Six years later, she was given in marriage to Raymond of Poitiers who died in 1149.Template:Sfn The widowed Constance's marriage to Raynald is described as "the misalliance of the century" by Hamilton,Template:Sfn but Buck emphasises that "the marriage went unmentioned in Western chronicles".Template:Sfn Buck adds that Raynald's relatively low birth "actually made him the ideal candidate" to marry the widowed princess who had a son with a strong claim to rule upon reaching the age of majority, and Raynald was possibly "expected to eventually step aside".Template:Sfn

The daughter of Raynald and Constance, Agnes, moved to Constantinople in early 1170 to marry Alexios-Béla, the younger brother of Stephen III of Hungary, who lived in the Byzantine Empire.Template:Sfn Agnes was renamed Anna in Constantinople.Template:Sfn Her husband succeeded his brother as BélaTemplate:NbspIII of Hungary in 1172.Template:Sfn She followed her husband to Hungary, where she gave birth to seven children before she died around 1184.Template:Sfn Raynald and Constance's second daughter, Alice, became the third wife of Azzo VI of Este in 1204.Template:Sfn Raynald also had a son, Baldwin, from Constance, according to Hamilton and Buck, but Runciman says that Baldwin was Constance's son from her first husband.Template:SfnTemplate:SfnTemplate:Sfn Baldwin moved to Constantinople in the early 1160s.Template:Sfn He died fighting at the head of a Byzantine cavalry regiment in the Battle of Myriokephalon on 17Template:NbspSeptember 1176.Template:Sfn

Raynald's second wife, Stephanie of Milly, was the youngerTemplate:Sfn daughter of Philip of Milly, Lord of Nablus, and Isabella of Oultrejordain.Template:Sfn She was born around 1145.Template:Sfn Her first husband, HumphreyTemplate:NbspIII of Toron, died around 1173.Template:Sfn She inherited Oultrejordain from her niece, Beatrice Brisbarre, shortly before she married Miles of Plancy in early 1174.Template:Sfn Miles of Plancy was murdered in October 1174.Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

Historiography and perceptions

Most information on Raynald's life was recorded by Muslim authors, who were hostile to him.Template:Sfn Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad described him as a "monstrous infidel and terrible oppressor"[2] in his biography of Saladin.Template:Sfn Saladin compared Raynald with the king of Ethiopia who had tried to destroy Mecca in 570 and was called the "Elephant" in the Surah Fil of the Quran.Template:Sfn Ibn al-Athir described him as "one of the most devilish of the Franks, and one of the most demonic", adding that Raynald "had the strongest hostility to the Muslims".Template:Sfn Islamic extremists still regard Raynald as a symbol of their enemies: one of the two mail bombs hidden in a cargo aircraft in 2010 was addressed to "Reynald Krak" in clear reference to him.Template:Sfn

Most Christian authors who wrote of Raynald in the 12th and 13th centuries were influenced by Raynald's political opponent, William of Tyre.Template:Sfn The author of the Template:Lang stated that Raynald's attack against a caravan at the turn of 1186 and 1187 was the "reason of the loss of the Kingdom of Jerusalem".Template:Sfn Modern historians have usually also treated Raynald as a "maverick who did more harm to the Christian than to the [Muslim] cause".Template:Sfn Runciman describes him as a marauder who could not resist the temptation presented by the rich caravans passing through Oultrejordain.Template:Sfn He argues that Raynald attacked a caravan during the 1180 truce because he "could not understand a policy that ran counter to his wishes".Template:Sfn Cobb introduces Raynald as the Template:Nobreak nemesis of Saladin", adding that Raynald's provocative actions inevitably led to Saladin's fatal invasion against the Kingdom of Jerusalem.Template:Sfn Along with Guy of Lusignan and the Knights Templar, Raynald is one of the negative characters in the Kingdom of Heaven, an epic action movie directed by Ridley Scott and released in 2005. Portrayed by Brendan Gleeson,Template:Sfn Raynald is presented in the film as an aggressive Christian fanatic who deliberately provokes a conflict with the Muslims to achieve their total destruction.Template:Sfn

Some Christian authors regarded Raynald as a martyr for the faith.Template:Sfn After learning of Raynald's death from King Guy's brother Geoffrey of Lusignan, Peter of Blois dedicated a book (entitled Passion of Prince Raynald of Antioch) to him shortly after his death. The Passion underlines that Raynald defended the True Cross at Hattin.Template:Sfn Among modern historians, Hamilton portrays Raynald as "an experienced and responsible crusader leader" who made several attempts to prevent Saladin from uniting the Muslim realms along the borders of the crusader states.Template:Sfn His comments are described by Cobb as "attempts to dispel" Raynald's "bad press".Template:Sfn The historian Alex Mallett refers to Raynald's naval expedition as "one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of the Crusades, and yet one of the most overlooked".Template:Sfn In 2017, the journalist Jeffrey Lee published a biography about Raynald, entitled God's Wolf,Template:Refn presenting him, according to the historian John Cotts,Template:Sfn in a nearly hagiographic style as a loyal, valiant, and talented warrior. Lee's book was praised by James Delingpole—a blogger associated with Breitbart—who attributed Raynald's bad reputation in the Western world to "cultural self-hatred",Template:Sfn but historians such as Matthew Gabriele sharply criticised Lee's approach. Gabriele concludes that Lee's book "does violence to the study of the past" due to his uncritical use of primary sources and his obvious attempt to make a connection between medieval history and 21st-century politics.Template:Sfn

Notes

References

Sources

Primary sources

- The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from Al-Kamil Fi'l-Ta'rikh (Part 2: The Years 541–582/1146–1193: The Age of Nur ad-Din and Saladin) (Translated by D. S. Richards) (2007). Ashgate. {{#invoke:CS1 identifiers|main|_template=isbn}}.

- The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin or al-Nawādir al-Sultaniyya wa'l-Maḥāsin al-Yūsufiyya by Bahā' ad-Dīn Yusuf ibn Rafi ibn Shaddād (Translated by D. S. Richards) (2001). Ashgate. {{#invoke:CS1 identifiers|main|_template=isbn}}.

Secondary sources

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

Further reading

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

- Template loop detected: Template:Cite book

Template:S-start Template:S-hou Template:S-reg Template:S-bef Template:S-ttl Template:S-aft Template:S-end

- Pages with template loops

- 1120s births

- 1187 deaths

- 12th-century princes of Antioch

- 12th-century French nobility

- Lords of Oultrejordain

- Christians of the Second Crusade

- Prisoners and detainees of the Ayyubid Sultanate

- Medieval French knights

- French Roman Catholics

- People from Loiret

- House of Châtillon

- Deaths by decapitation

- Remarried jure uxoris officeholders

- Jure uxoris lords

- Jure uxoris princes